Frequently and alternatively called the Camp Logan Mutiny, this riot and mutiny remains the largest mutiny and murder proceedings in American history. It was 1917 in Texas, which still had Jim Crow laws on the books, and the soldiers who were stationed at Camp Logan, just outside of Houston, reached a boiling point after several African-Americans were beaten and arrested by the police.

Feature Article

The Camp Logan Mutiny

In 1917, shortly after the United

States declared war on Imperial Germany,

the War Department ordered the Third Battalion of the 24th United States

Infantry Regiment, an all-black unit of the famous Buffalo Soldiers, to

guard the construction

site of Camp Logan in Houston,

Texas.

At that time, the armed services were segregated, and racial

discrimination was accepted in many places in America. Texas

was one of them.

On the afternoon on August 23, two policemen

fired a warning shot before they burst into the home of a black woman

saying they were looking for a man who was accused of participating in a gambling

venture.

The police accused her of harboring the man and dragged her, barely clad,

into the street. Her five children watched as their mother was assaulted

in the street.

A crowd began to assemble, and Alonso Edwards, a soldier from the 24th

Infantry, was among the crowd. He asked patrolman Lee Sparks what was

happening and asked if he could fetch the woman some clothes. Sparks

pistol-whipped Alonso Edwards, beat him to the ground, and arrested him for

"interfering with the arrest of a publicly drunk female."

Later in the afternoon, Corporal Charles Baltimore, a military

policeman from the 24th, went to the police station to try to get Edwards

released. The discussion he was having with the police turned violent, and

Corporal Baltimore was himself shot at, beaten, and arrested. He was

released a bit later, but the men at the camp were unaware of that fact,

and rumors that Baltimore had been beaten, or possibly murdered by the

police flourished.

As things began to get out of control at the camp, a battalion commander

ordered all soldiers to be confined to the camp. He then ordered four

first sergeants to collect all ammunition and rifles.

A group of 156 soldiers, angry at the violence and racism, marched on the

City

of Houston intending to storm the police station and free their

comrade. Before they left, however, they stole guns from the supply tent.

Reportedly, one of the first sergeants, Vida Henry, joined the angry mob

of soldiers.

The police and citizenry of Houston

had heard reports of a mutiny and made their way, armed as well, toward

the camp.

As the soldiers marched toward the police station, they fired into the

night after someone shouted, "Here they come!" A white child was hit by a

stray bullet and died. An Army Captain was the next victim, and there is

speculation that he was mistaken for a policeman. Then one of the

policemen who was involved in the beating and arrest of Corporal Baltimore

was killed.

Around this time, many of the soldiers fell away from the marching mob,

some hiding and some heading back to camp. First Sergeant Henry dropped

out and was later found dead

from a self-inflicted gunshot.

The ensuing riot left four soldiers, four policemen, and twelve civilians

dead.

Martial law was declared, and two days later, the battalion was on a train

back to New

Mexico. When they arrived, 118 of the soldiers were arrested,

charged with mutiny and murder, and taken to the stockade in El

Paso, Texas at Fort Bliss, where they awaited their courts martial.

The rest of the unit was transferred to the Philippines.

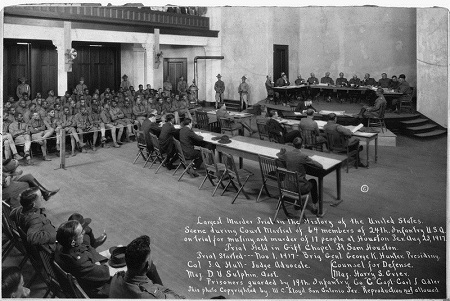

In all, 198 witnesses -- 169 for the prosecution and 29 for the defense --

testified, including seven of the soldiers who agreed to testify after

being promised clemency. In all, three separate courts-martial were

conducted. The first was held at Fort Sam Houston in San

Antonio. The proceedings were held in the chapel, which could only

hold trial for 63 men.

All of them were represented by one lawyer,

on charges of disobeying orders, aggravated assault, murder, and mutiny.

On November 28, thirteen of the defendants were sentenced to be hanged on

December 11, though they themselves were not told of the sentences until

December 9. Life sentences were given to 41 soldiers, four were given

shorter sentences, and five were found not guilty.

The gallows were hastily built, and at 7:17 in the morning, one minute

before sunrise, they were hanged, all at the same moment.

The soldier who had guarded the condemned prisoners was a white

infantryman, who described the scene like this:

"The doomed men were taken off the trucks, not one making the slightest

attempt to resist...The unlucky thirteen were lined up...As the ropes were

being fastened about the men's necks, big (Private Frank) Johnson's voice

suddenly broke into a Christian

hymn -- 'Lord, I'm Comin' Home' -- and the others joined him. The eyes of

even the hardest of us were wet."

After this incident, a new military rule, General Order No. 7, was

issued, mandating that all death

sentences would be suspended until the President of the United

States officially reviewed all of the pertinent records.

Then the second court martial -- with 15 soldiers standing accused -- took

place from December 17 through December 22, 1917. Five of them were found

guilty and sentenced to death.

The third took place from February 18 until March 26, 1918, with 40

soldiers standing accused. Eleven were sentenced to hanging and the

remainder to life in prison.

So, in all, 118 enlisted men were court-martialed for having taken part in

the mutiny. 110 of them were found guilty: 29 were sentenced to die for

their participation and 81 were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives

in prison.

President Woodrow Wilson commuted

the death sentences of ten of the condemned soldiers to life in

prison. He publicly said that he had affirmed the death sentences of

the six remaining soldiers as their was "plain evidence" that they had

participated in the brutal riot.

And so it was that five more soldiers were hanged at dawn, and the sixth

and final condemned man was executed a week later, again at dawn.

While looking into the history

of the 24th Infantry for this article -- once part of the legendary

Buffalo Soldiers -- I did not run into a single piece of writing

which did not mention the riot and mutiny, though there are a few which

refer only fleetingly to "the trouble in Houston."

The area where Camp Logan was situated is now an upscale neighborhood

called Memorial Park and has nothing more than a single marker to

commemorate what happened there in 1917.

Recommended Resources

Coming Home from Battle to Face a War

Subtitled "The Lynching of Black Soldiers in the World War I Era," this dissertation has a chapter dedicated to the Texas race riots, including Fort Logan as well as the Brownsville riots.

http://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3794&context=etd

Racial Violence and Segregated Armed Forces

This section of African Americans and World War I is about the Houston Riots and mutiny as well as the results of that chapter in history.

http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-world-war-i.html#racial

South Texas College of Law: Houston Mutiny & Riot

This is a collection of records regarding one of the largest race riots in United States history, the riots at Camp Logan.

http://libguides.stcl.edu/content.php?pid=181515&sid=1526772

The Houston Mutiny and Riot of 1917

This manuscript, 23 pages in length, delves deeply into the Camp Logan riot and mutiny. One may read the entire manuscript online for free or pay $24.00 to download it.

http://studythepast.com/civilrightsundergraduate/materials/houston_riot_of_1917.pdf